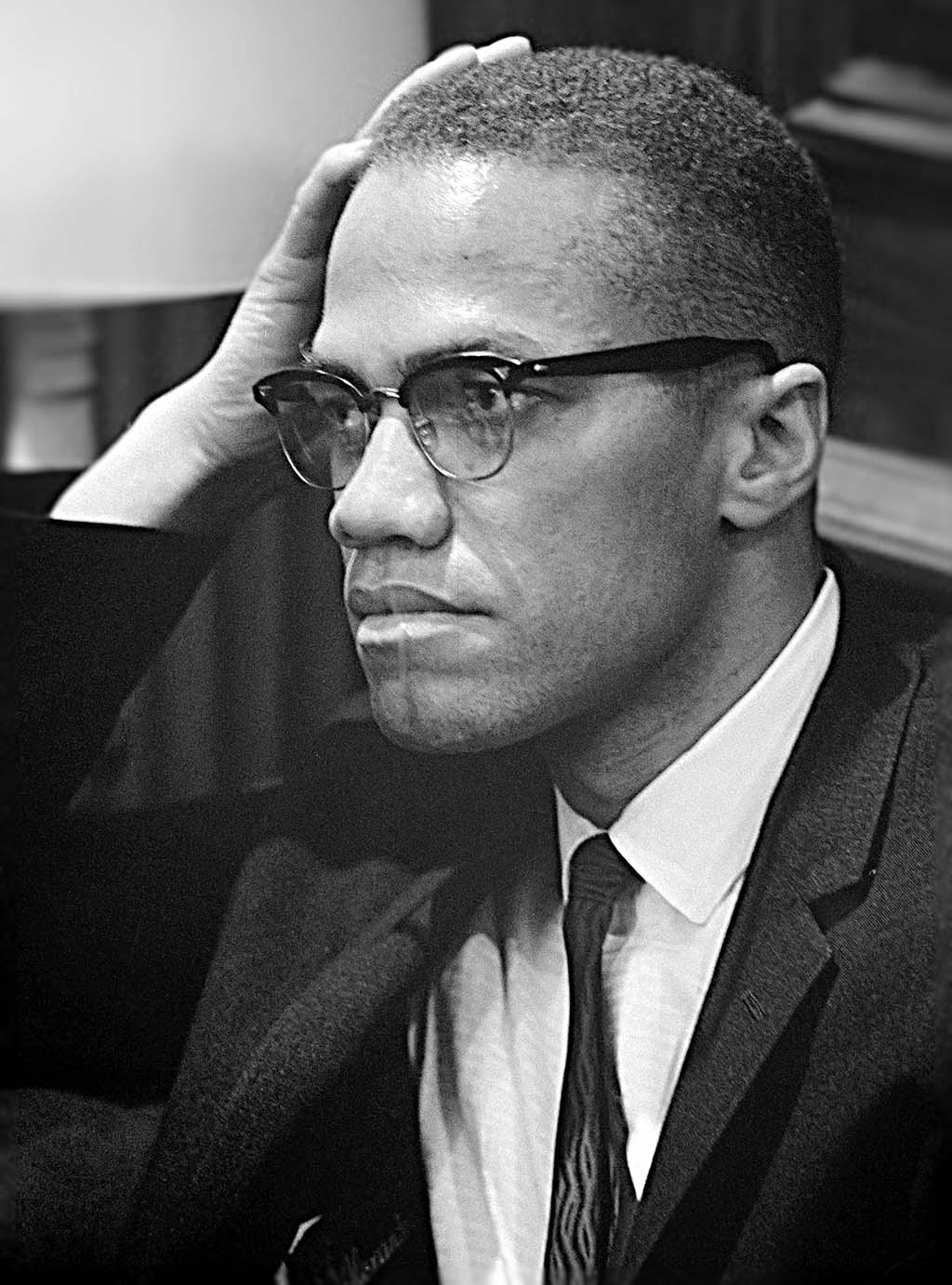

Malcolm X, one of the most influential African American leaders of the 20th Century, was born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska on May 19, 1925 to Earl Little, a Georgia native and itinerant Baptist preacher, and Louise Norton Little who was born in the West Indian island of Grenada. Shortly after Malcolm was born the family moved to Lansing, Michigan. Earl Little joined Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) where he publicly advocated black nationalist beliefs, prompting the local white supremacist Black Legion to set fire to their home. Little was killed by a streetcar in 1931. Authorities ruled it a suicide but the family believed he was killed by white supremacists.

Although an academically gifted student, Malcolm dropped out of high school after a teacher ridiculed his aspirations to become a lawyer. He then moved to the Roxbury district of Boston, Massachusetts to live with an older half-sister, Ella Little Collins. Malcolm worked odd jobs in Boston and then moved to Harlem in 1943 where he drifted into a life of drug dealing, pimping, gambling and other forms of “hustling.” He avoided the draft in World War II by declaring his intent to organize black soldiers to attack whites which led to his classification as “mentally disqualified for military service.”

Malcolm was arrested for burglary in Boston in 1946 and received a ten year prison sentence. There he joined the Nation of Islam (NOI). Upon his parole in 1952, Malcolm was called to Chicago, Illinois by NOI leader, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Like other converts, he changed his surname to “X,” symbolizing, he said, the rejection of “slave names” and his inability to claim his ancestral African name.

Recognizing his promise as a speaker and organizer for the Nation of Islam, Muhammad sent Malcolm to Boston to become the Minister of Temple Number Eleven. His proselytizing success earned a reassignment in 1954 to Temple Number Seven in Harlem. Although New York’s one million blacks comprised the largest African American urban population in the United States, Malcolm noted that “there weren’t enough Muslims to fill a city bus. “Fishing” in Christian storefront churches and at competing black nationalist meetings, Malcolm built up the membership of Temple Seven. He also met his future wife, Sister Betty X, a nursing student who joined the temple in 1956. They married and eventually had six daughters.

Malcolm X quickly became a national public figure in July 1959 when CBS aired Mike Wallace’s expose on the NOI, “The Hate That Hate Produced.” This documentary revealed the views of the NOI, of which Malcolm was the principal spokesperson and showed those views to be in sharp contrast to those of most well-known African American leaders of the time. Soon, however, Malcolm was increasingly frustrated by the NOI’s bureaucratic structure and refusal to participate in the Civil Rights Movement. His November 1963 speech in Detroit, “Message to the Grass Roots,” a bold attack on racism and a call for black unity, foreshadowed the split with his spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad. However, Malcolm on December 1, in response to a reporter’s question about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, used the phrase “chickens coming home to roost” which to Muslims meant that Allah was punishing white America for crimes against black people. Whatever the personal views of Muslims about Kennedy’s death, Elijah Muhammad had given strict orders to his ministers not to comment on the assassination. Malcolm defied the order and was suspended from the NOI for ninety days.

Malcolm used the suspension to announce on March 8, 1964, his break with the NOI and his creation of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. Three months later he formed a strictly political group (an action expressly banned by the NOI), called the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) which was roughly patterned after the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

His dramatic political transformation was revealed when he spoke to the Militant Labor Forum of the Socialist Workers’ Party. Malcolm placed the Black Revolution in the context of a worldwide anti-imperialist struggle taking place in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, noting that “when I say black, I mean non-white—black, brown, red or yellow.” By April 1964, while speaking at a CORE rally in Cleveland, Ohio, Malcolm gave his famous “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech in which he described black Americans as “victims of democracy.”

Malcolm traveled to Africa and the Middle East in late Spring 1964 and was received like a visiting head of state in many countries including Egypt, Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya, and Ghana. While there, Malcolm made his hajj to Mecca, Saudi Arabia and added El-Hajj to his official NOI name Malik El-Shabazz. The tour forced Malcolm to realize that one’s political position as a revolutionary superseded “color.”

The transformed Malcolm reiterated these views when he addressed an OAAU rally in New York, declaring for a pan-African struggle “by any means necessary.” Malcolm spent six months in Africa in 1964 in an unsuccessful attempt to get international support for a United Nations investigation of human rights violations of Afro Americans in the United States. In February 1965, Malcolm flew to Paris, France to continue his efforts but was denied entry amidst rumors that he was on a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) hit list. Upon his return to New York, his home was firebombed. Events continued to spiral downward and on February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan.