The Negro Boys Industrial School Fire, also known as the Wrightsville Fire, occurred on March 5, 1959, at the Negro Boys Industrial School (NBIS), a juvenile correctional facility for Black male youth located near Wrightsville, Arkansas. On that tragic day, twenty-one African American boys died in a dormitory fire at the facility.

The NBIS was originally established to house juvenile delinquents who would otherwise have been sent to adult prisons. Most of the boys placed there had been charged with minor offenses, were from broken homes, or simply had no other place to go. The boys resided in a 1936 Works Progress Administration building known to be in deplorable condition. A 1956 report by sociologist Gordon Morgan documented the appalling conditions at the institution: “Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during the winter of 1955–56. It is not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, who visited the facility in January 1958, remarked, “They really need help. They are using some old wood stoves which should be replaced.”

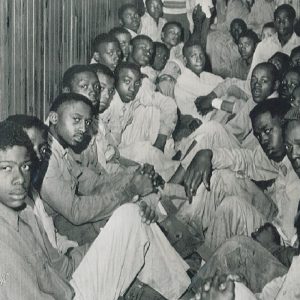

Negro Boys Industrial Fire. Photo of Boys (Equal Justice Initiative)

The fire began around 4:00 a.m. on March 5, 1959, in the dormitory. Of the forty-eight boys, aged thirteen to seventeen, twenty-seven managed to escape by jumping from windows. The remaining twenty-one were trapped inside and burned to death. Although an investigation was launched, the authorities never determined the cause of the fire. It was discovered that the dormitory doors had been locked from the outside, making escape nearly impossible for those trapped inside. Some speculated that the fire may have been the result of the building’s deteriorating condition.

Wrightsville School Dormitory (CNN)

At a morning press conference following the fire, Governor Faubus placed blame for the tragedy on Lester R. Gaines, the Black superintendent of the facility. He criticized Gaines for not ensuring that an employee was present in the dormitory at night in case of emergencies. Gaines refused to resign, stating that he would not step down unless formally asked to do so. Eleven employees supported Gaines, signing a statement published in the Arkansas State Press. Nonetheless, the board chairman, Alfred Smith, terminated Gaines and several other employees, as recommended by Governor Faubus.

A committee was appointed to investigate the fire. It concluded that the correctional facility, the State of Arkansas, and the local community all shared responsibility for the incident. However, the committee recommended no specific course of action. A Pulaski County grand jury questioned witnesses but returned no criminal indictments.

Wrightsville School Plaque (Encyclopedia of Arkansas)

The tragedy was largely forgotten until nearly fifty years later, when Frank Lawrence, the brother of one of the victims, began working on a documentary about the fire in 2019. Joined by other family members, he sought to bring attention to the forgotten tragedy and provide a sense of closure. That same year, a monument honoring the twenty-one boys who died was unveiled at the Wrightsville Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction, located on the site of the original facility, which closed in 1968.